Crownland

Czechs cling to revered national currency

Bulgaria joined the euro on January 1. The Czech Republic didn’t.

This is not - by any stretch of the imagination - news.

Since becoming a member of the EU on May 1, 2004, Czech governments have shown almost no interest whatsoever in the single European currency.

Each successive cabinet - Špidla, Gross, Paroubek, Topolánek I, Topolánek II, Fischer, Nečas, Rusnok, Sobotka, Babiš I, Babiš II and Fiala - has either postponed, avoided or explicitly opposed setting a concrete date for euro adoption, despite it being a treaty obligation for all new EU member states under the terms of accession.

The latest government - the thirteenth since joining the EU - has gone even further.

Euro - ¡No pasarán!

As I wrote for Deutsche Welle this week, Andrej Babiš’s new cabinet has made a solemn pledge to the Czech people.

Not only will they take no steps at all towards entering the Eurozone (all that boring Maastricht criteria stuff), they will actually try to change the constitution to ensure the Czech crown remains the national currency forever.

In reality, parliamentary arithmetic makes this a largely futile endeavour. They don’t have the votes. A constitutional change will likely never happen.

It’s more red meat for voters of the viscerally Eurosceptic SPD and Motorists for Themselves - Babiš’s coalition partners.

But neither will Czechs be any closer to paying with euros by the time Babiš III hands over to the next government (sometime in late 2029, if it lasts a full term).

Professor Calculus

I have to admit the constant dithering over the euro used to bother me. It was in the Terms and Conditions. You joined the club. Follow the rules.

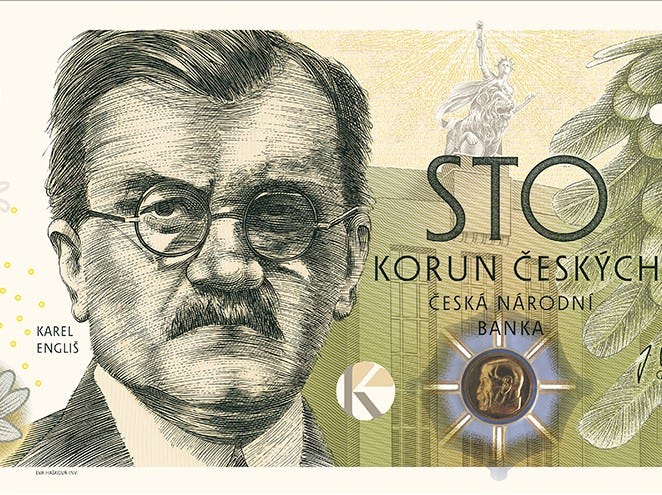

But now? Frankly, I’ve come to rather love the koruna česká. I don’t mean the fiscal and monetary side of it - my expertise in that area is zero. I mean the actual notes and coins. I like the pictures.

I enjoy gazing at the portrait of Charles IV on the 100 crown note. He looks pensive, as if caught in an unguarded moment. I savour the cut of Palacký’s jaw on the 1,000. He was clearly not a man to be messed with. I giggle at Masaryk’s goatee on the 5,000. His expression gives strong Professor Calculus vibes. (Sorry TGM, I’m aware this is sacrilege).

In fact, I’ve always had a weakness for interesting legal tender (this may not come as a total surprise given my map obsession).

Somewhere I have a photo of my travelling companion Benny inside a tent in South Bohemia in the summer of 1992 - a summer that marked the beginning of the rest of my life.

A mountain of money

He is decorated - festooned - in Czechoslovak banknotes and the silly souvenirs we had bought with them; chocolate bars, postcards of Zetor tractors, cheap Sparta cigarettes.

They were the big old green 100 Czechoslovak crown banknotes featuring a steelworker and a collective farm worker on one side, and an image of Charles Bridge and Prague Castle on the other.

They were the highest-denomination banknotes we’d ever held in our lives, and we had fistfuls of them. They made us feel enormously rich and powerful (together they were probably worth about £50).

Working as a journalist subsequently gave me numerous opportunities to delve into the history of money in this country. And some of it is downright fascinating.

Consider the dollar.

The most powerful currency in the world began life - improbably - in a West Bohemian mining town called Jáchymov.

Known to its German-speaking inhabitants as Joachimsthal (“Joachim’s Valley”), the coins minted from the rich silver deposits found nearby were officially called Joachimsthaler - literally “coins from Joachim’s Valley”.

Joachimsthaler was a bit of a mouthful even for 16th-century German settlers, so they soon shortened it to ‘thaler’ (‘tolar’ in Czech).

Coins from Joachim’s Valley

The large, reliable silver coins became widely accepted across Central Europe, and after a while most large, silver coins of a similar weight minted in medieval Europe were called ‘thalers’ (or variants thereof). In Dutch, they were called daalders.

Dutch traders carried the daalder to North America. English speakers then adapted the pronunciation to dollar.

By the late 18th century, dollar had become the common term in the American colonies for any large silver coin.

In 1792, the United States formally adopted dollar as the name of its currency.

I heartily recommend a visit to Jáchymov. It’s about half an hour by car from Karlovy Vary. The same mines (some are open to the public) later yielded the lump of uranium ore that Marie Curie used to isolate polonium and radium. So Jáchymov gave the world the dollar, nuclear physics and the atomic bomb. It’s quite the place.

But back to the euro. And the crown.

Slovakia - which has on occasion been regarded (condescendingly) as the Czech Republic’s ‘little brother’ - joined the EU on the same day as the Czechs; May 1, 2004. Within less than five years they’d adopted the euro.

Euro roadshow

I remember going on a Slovak government ‘roadshow’ in the final weeks before the switchover, which was pencilled in for January 1, 2009.

A guy called Martin was driving a transit van across southern Slovakia trying to persuade sceptical locals of the benefits of ditching the (Slovak) crown for the euro. It was a tough sell.

But 17 years on, that uncertainty has evaporated. It’s gone.

I’ve still got a freshly minted Slovak one euro coin on the shelf above my desk. The Finance Ministry was giving them out to journalists. It’s in a little felt box. It’s got the Slovak double cross - the dvojkríž - on the obverse.

I wonder whether I’ll ever get a Czech one to add to my collection.

Somehow I doubt it.

Very interesting. One of my favourite stories of renaissance Bohemia is that of the copper-smelter Joachim Gans (whose name pleasingly echoes that of Joachimstaler, although he came from Prague). He was the first Jew in America.

A nice piece – thank you for putting Joachimsthal on my radar. I share your appreciation for the regional currencies as pieces of public art in and of themselves. When my girlfriend and I began dating, I noticed she was paying for everything in 20 lei (~4€) banknotes. The notes had been issued just a few years before and were the first in Romania to bear a woman. She took a special liking to them and requests them over other bills from the ATMs here wherever possible. I hear there are other women doing the same.