Maps matter

Expansionism and revanchism on full display

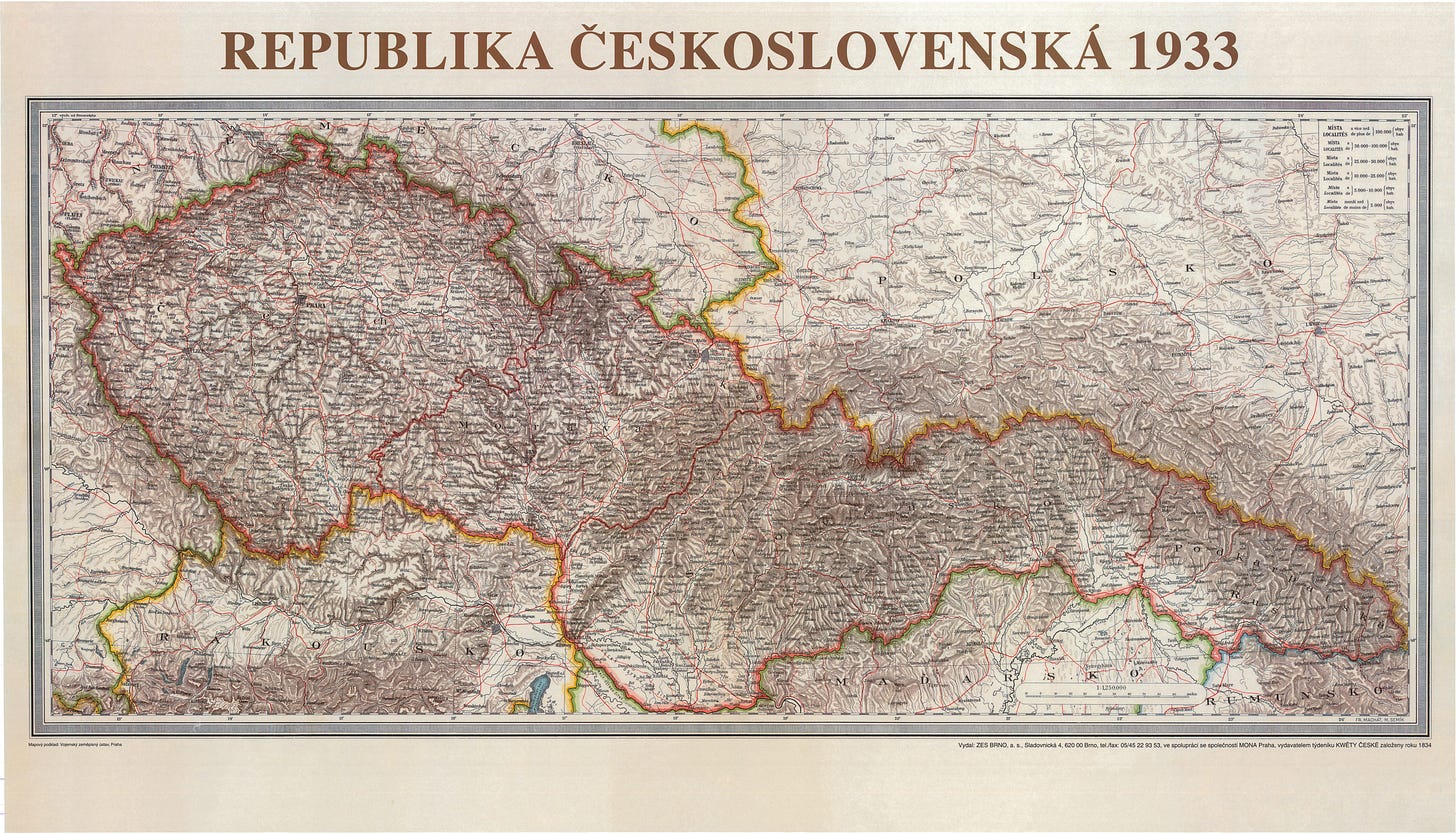

There’s a map above my desk. It’s one of my favourites. It shows Czechoslovakia in 1933, the year Hitler seized power across the border.

It was created by cartographers František Machát and Matěj Semík, and printed by the Military Geographic Institute in Prague.

In quiet moments, when I’m struggling to write a sentence, my gaze inevitably wanders up from the blinking cursor.

I follow the intricate contour lines, tracing the topography of mysterious Moravian valleys and silently mouthing the names of obscure Slovak villages.

Sometimes, my eyes dart across the border to Poland. When I’m in a particularly mournful frame of mind, I’ll see if I can trace the black lines to the railway junction at Oświęcim.

This map almost got me into trouble once.

Occasionally I do TV lives from home rather than outside on the street. I’ll often be looking for a suitable backdrop. Usually it’s the inevitable bookcase. But once, I chose the map.

“That’s a funny map, I don’t think I’ve seen Czechoslovakia looking like that before,” said the BBC editor in London.

“It’s because it’s still got Sub-Carpathian Ruthenia on it - Stalin seized it from them in 1945 and stuck it onto the Soviet Union,” I answered.

“Ah,” he replied. “Well, do you think you could sit somewhere else? We don’t want to be seen to be supporting Czechoslovak revanchism.”

I thought he was joking. He wasn’t. I chose the bookcase.

There’s another, bigger map downstairs in the living room. It’s a reproduction of Gustav Freytag’s magnificent Karte von Oesterreich-Ungarn, published by Freytag und Berndt in Vienna in 1891.

It shows the Austro-Hungarian Empire in all of its multi-faceted, multi-national glory, with a handful of southern neighbours - Italien, Serbien, Romanien - pressed up uncomfortably against it.

Most of the map is taken up by the Kingdom of Hungary. It extends over a vast swathe of Central Europe to include what is now all of Slovakia (Felvidék, or Upper Hungary), much of Romania (Transylvania), Croatia (Slavonia) and Serbia (Vojvodina), the western tip of Ukraine (Carpathian Ruthenia), a slice of eastern Austria (Burgenland) and a sliver of Slovenia.

You can spend hours gazing at this map. I once found our Ukrainian cleaning lady poring over it, trying to locate her home village in what was then the Hungarian region of Kárpátalja but is now Zakarpattia Oblast in Ukraine.

She’d found a large town called Munkács, which seemed familiar but she couldn’t quite place it. We Googled it. “Ah!” she cried. “Mukachevo!” Now she knew where she was. We went back to our respective tasks.

Then came 1920 and the Treaty of Trianon, and all of these Hungarian crown lands were lost. Around three million ethnic Hungarians were left stranded outside them, looking forlornly towards Budapest. It’s an event still regarded in Hungary as a national catastrophe.

There was a brief revision during the war, when land was torn from Czechoslovakia and Romania and reattached to (Axis) Hungary.

But it was not to last. Once again, Budapest found itself on the losing side. Hungary shrank back to its 1920 frontiers, and they’ve remained untouched ever since. Viktor Orbán may have expanded in recent decades, but Hungary has not.

The centenary of Trianon was marked by the unveiling of a sombre ‘Togetherness Memorial’ in the heart of Budapest, bearing the (Hungarian) names of all the ‘lost’ towns and villages.

But a few years later Orbán went further, appearing at a Greece-Hungary friendly in a ‘Greater Hungary’ football scarf, showing the country in its pre-Trianon borders. Images and video were shared by his office on social media in case anyone missed it. There were diplomatic protests from Romania and Ukraine.

In 2024, Hungary’s ambassador to NATO distributed atlases festooned with maps of pre-Trianon Hungary as gifts to alliance colleagues; this time the howls of outrage came from Romania and Croatia.

And in 2025, Hungary’s state-owned M1 television channel broadcast the national anthem accompanied by stirring images of the Hungarian countryside and famous Hungarian landmarks including … Bratislava Castle. The Slovak opposition expressed their disgust. The Fico government - aligned with Orbán - was silent.

Hungary is obviously not the only country to indulge in such high-level trolling; nationalist politicians in Poland, Romania and Serbia have been known to brandish a provocative map to get a rise out of the neighbours.

In 2022, a Czech MEP caused much mirth by joking that Prague had a legitimate claim to the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad because it was founded (in 1255) in honour of the Bohemian king Přemysl Otakar II. He suggested a joint Czech-Polish force could annex it and return it to its historical Czech name: Královec. It became a meme; even the Ukrainian government joined in the fun. Moscow fumed.

But it was never more than some wags on Twitter. Likewise, no one seriously expects Hungary to march into one of its NATO neighbours, or try to reoccupy Serbia’s Vojvodina or Ukraine’s Zakarpattia region.

Russia, however, is another matter altogether.

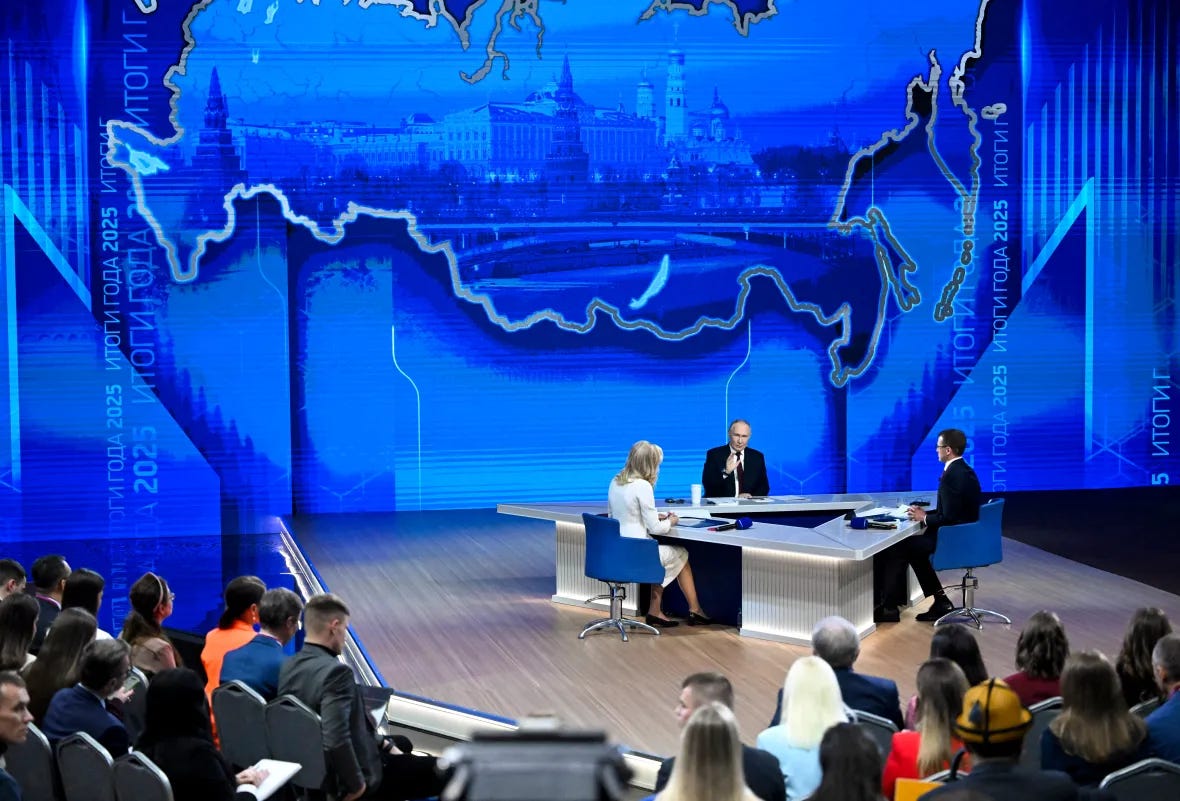

When Vladimir Putin appeared at his annual end-of-year news conference in December, eagle-eyed observers quickly noticed the contours of the map serving as the backdrop.

It wasn’t the first time that the big blue map included the five Ukrainian territories - Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson - that Russia has ‘annexed’ (but only partially controls).

But if you needed a clearer signal that Putin has no intention of stopping the war until he has achieved his maximalist aims, you’d be hard pressed to find one.

It’s right up there on the wall behind him.

Fine piece, thanks Rob

Nice text, thank you! Though can't agree on

> Likewise, no one seriously expects Hungary to march into one of its NATO neighbours, or try to reoccupy Serbia’s Vojvodina or Ukraine’s Zakarpattia region.

Considering for example:

>The spies had also been gathering information on the public sentiment among local residents to predict their response in the event of a Hungarian incursion, according to the SBU.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy8dx16q3nzo