The cold hard ground

Prague's cemeteries bury many a secret

A daughter’s shriek. A rush of feet. A lifeless rodent in its cage.

This is how death came to our house in the closing weeks of last year.

It prompted what can only be described as a series of technical and administrative tasks. The kind of tasks dads are called upon to perform in these situations.

One of them was disposing of a large and perfectly serviceable cage. Thankfully an animal-loving friend wanted it, and I soon found myself navigating Prague’s northern suburbs.

I drove past the sprawling cemetery at Ďáblice - for the second time in a matter of weeks.

Praha–Žatec

I’d been there in November to watch archaeologists from the Prague City Museum begin excavating a mass grave in the hope of identifying three Czechoslovak army officers who were hanged at Prague’s Pankrác prison in 1949.

The three were key figures in an abortive anti-Communist uprising known as ‘Praha–Žatec’ that planned to take over the West Bohemian garrison town of Žatec and lead an assault on the nascent Stalinist government in Prague.

The group was infiltrated by the Communist secret police and caught before they could launch the uprising. They were convicted of high treason and executed.

Their bodies were reportedly deposited in Mass Grave No. 14 at Ďáblice, a ‘social grave’ containing 281 corpses: drifters, stillborn babies, people who’d died in hospital with no one to bury them.

Several relatives of the officers were present on the first day of the dig, hoping for closure.

It hasn’t come.

The last I heard, the archaeologists were coming to terms with the fact they were probably excavating the wrong grave, judging by the remains they had so far succeeded in identifying. The records are patchy. Work was on hold for the winter.

The man behind the dig is a guy called Jiří Línek, head of the Association of Former Political Prisoners 1948–1989.

Jiří has made it his life’s work to bring some clarity to this mournful chapter in Czech history; there are perhaps several hundred Communist-era political prisoners buried here in anonymous graves. He wants to give them a proper burial.

But it’s not just the Communist era.

Anthropoid

The excavations - if they continue, and if they are successful - could ultimately recover the remains of the seven Czechoslovak paratroopers involved in Operation Anthropoid, the assassination of acting Nazi Reichsprotektor Reinhard Heydrich in May 1942.

As I wrote for the BBC back in 2016, historians believe their seven corpses were decapitated by the Gestapo; the heads of the two men who ambushed Heydrich - Jan Kubiš and Jozef Gabčík - were kept in formaldehyde at the Prague Institute of Pathology. The skulls of the remaining five were also preserved.

The heads were last seen being loaded onto a goods train at Prague’s Smíchov station on April 20, 1945. It was Hitler’s birthday. They’ve never been seen since.

The bodies - it is thought - were dumped at Ďáblice. But no-one knows for sure.

I live in Žižkov, just round the corner from the Prague TV Tower .

It’s an incredible piece of architecture. A space-age emblem of the Czech capital. I love it.

But at its feet there’s a dark history.

Bulldozed graves

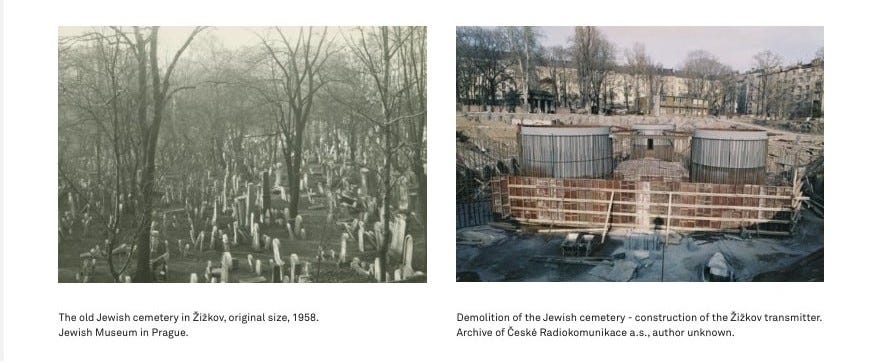

The TV tower was built in the 1980s on the site of what had been one of Prague’s largest Jewish cemeteries.

The cemetery in Fibichova Street was established in 1680 as a burial ground for Jewish victims of the plague. It subsequently became the Jewish community’s main graveyard and remained so until the late 19th century. Some 40,000 people were laid to rest here.

The last burial was in 1890, when the New Jewish Cemetery at Olšany opened (this is where Franz Kafka is buried).

After World War II, with the Jewish community decimated by the Holocaust, the Fibichova cemetery fell into neglect. Thanks to the efforts of the indefatigable researcher Martin Šmok, we now know more about what followed.

In the 1960s, the authorities decided to clear the area and create a public park - Mahlerovy sady. Tombstones were laid flat and covered in earth, under the watchful eyes of a rabbi.

In the 1980s, however, when the TV tower project received the green light, far less care was given to Jewish sensitivities.

The bulldozers and diggers moved in to dig the foundations, holes were filled in with concrete. Some remains were reburied in the New Jewish Cemetery, others were taken to a dump.

Today, to add insult to injury, there’s a minigolf course at the foot of the tower, built round the edges of the park.

Martin says that according to the documents, there are most likely still some remains lying just beneath the putting holes.

He once took me on a tour of the site - including the oldest section of the cemetery, which was preserved. It’s now a popular pilgrimage site for devotees of 18th century Rabbi Ezekiel Landau (Noda bi-Yehuda). You can listen here:

Bohnice - the empire’s graveyard

But perhaps the most mysterious graveyard of them all is the abandoned cemetery that once belonged to Bohnice psychiatric hospital.

Walking through this sprawling, overgrown place is an eerie experience even on a bright spring day. It is the most liminal of liminal spaces.

Miloš Forman shot Mozart’s funeral scene here for Amadeus, and it has lost none of its melancholy emptiness. The last burials were in the mid-1960s.

I was shown around a few years ago by local historian Jiří Vítek. He’s also the deputy mayor of Prague 8 - the city district that now owns the site. He’s spent years cleaning up the cemetery and raising money to restore it.

Bohnice Institutional Cemetery was established in 1909 for people who died at Bohnice Hospital, at that time the largest psychiatric institution in Austria-Hungary. Patients came from across the empire - Bohemia, Moravia, Austria, Hungary, Bosnia, Croatia, Slovenia, Italy.

Most of the graves were unmarked, or marked with a simple iron number (later stolen for scrap). Some 4,000 souls were laid to rest here.

In 1916, fighting raged in the Trentino in southern Tyrol, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Jiří explained that some 240 psychiatric patients were evacuated to Bohnice, bringing with them typhus that quickly caused an epidemic. In all, 640 patients are reported to have died and were later buried here at the cemetery.

A plaque to 48 Italian victims - crafted from Trentino marble - was installed in 1932. It was paid for personally by Benito Mussolini. Jiří told me it was later destroyed.

Archduke’s assassin

The most famous - or notorious - person buried here was Gavrilo Princip, the man who assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the event that sparked the First World War.

Princip was imprisoned in Terezin fortress, 50km north of Prague, and died there of tuberculosis in April 1918. He was buried at Bohnice - the ceremony is well documented.

But there are also claims his remains were later exhumed and reinterred in a Serbian Orthodox crypt in Sarajevo. It’s never been proven.

And finally the strangest mystery of all.

Some time in the mid-1990s, the cemetery is said to have received a VIP visitor.

The story was recounted to Jiří personally by a friend with an allotment next to the cemetery.

According to this friend, a convoy of limousines drew up in a cloud of dust one summer, and out stepped … Margaret Thatcher. At this point the former prime minister was Baroness Thatcher. She was described as wearing a trench coat and a scarf.

There was much consultation of cemetery plans and finally a grave was identified. The story goes she was looking for a distant relative of her husband Denis. Rumour has it some remains were later exhumed and returned to the UK.

I myself tried - and failed - to resolve this mystery.

Iron Lady

Thatcher made a number of visits to Prague in the 1990s. But the British Embassy had no such record of her visiting the cemetery.

So I wrote to Petr Macinka, now Foreign Minister but also the former spokesman of Václav Klaus, who was prime minister at the time. Klaus had no recollection of the incident either - and any such visit would surely have gone through his office.

Finally, I managed to track down an email address for Carol Thatcher, her daughter.

Could she shed any light on this most mysterious occurrence? Surely her mother would have mentioned travelling to Prague to exhume a relative of her father?

“I’m sorry,” she replied.

“I’ve got absolutely no idea what you’re talking about.”

Some of Bohnice’s secrets were evidently taken to the grave.

And remain there.