Description of a struggle

A Prague gallery documents the subjugation of Slovak culture

Bit of a cultural tip this week: if you want to know what happens when you put far-right populists in charge of your cultural institutions, check out the Prague City Gallery’s Dům fotografie in Revoluční.

As I wrote for Deutsche Welle this week, a new exhibition called Free National Gallery. Description of a Struggle documents the decline and fall of Slovakia’s national museum of art, the Slovak National Gallery (SNG).

And it carries an implicit warning for Czech culture too.

Alexandra Kusá had been director of the Slovak National Gallery for 14 years when Robert Fico formed his fourth administration in 2023. She’d been a curator there for the previous decade.

Well-regarded both at home and abroad, she had recently overseen an ambitious renovation project of the gallery’s main site in Bratislava, on the Danube embankment.

But when Martina Šimkovičová, elected as an MP for the nationalist Slovak National Party, was appointed as the new Minister of Culture, Alexandra could see the writing on the wall.

“The culture of the Slovak people should be Slovak. Slovak and no other. We tolerate other national cultures, but our culture is not a mixing of other cultures,” Šimkovičová told reporters in November 2023, setting out what would be her policy priorities.

It wasn’t long before she began purging Slovakia’s cultural scene of those she said were pushing a liberal agenda.

The director of the Slovak National Library was removed, followed by the director of the Slovak National Theatre.

Alexandra drafted a public letter of support to her colleague at the National Theatre.

She was fired the next day.

She laughed down the phone from Bratislava when she told me the official reasons for her sacking.

“First it was because the gallery was empty. Then because it was too full.”

“Then it was because there was no Slovak flag outside the building. Then it was because of the renovation work,” Kusá told me.

The ministry accused her of nepotism, because her architect father had been involved in drawing up the winning design.

He had indeed - in 2005, five years before she became director.

“They never announced the real reason, which is that they simply didn’t want to work with us. Which is a shame, because it was the truth.”

LGBT propaganda

Not that Alexandra held out much hope for a fruitful working relationship with the new minister.

Martina Šimkovičová rose to prominence during Covid, co-presenting a YouTube channel with her partner that offered a steady stream of disinformation about the virus and vaccines.

Today both are MPs, and enjoy senior positions in the Slovak government.

She has prioritised state support for what she calls ‘traditional Slovak values’ as opposed to ‘liberal’ art that pushes a minority agenda, such as LGBT rights.

“We heterosexuals are capable of creating the future, because we can have children, right?” she told an interviewer in 2024.

“Europe’s dying out, no new children are being born, because there’s an overload of LGBT people. And I think it’s strange that all this is happening to the white race.”

Her style of management is uncompromising. Witness her reaction to being asked by a reporter whether her decision to install a close friend as the new head of the Bibiana children’s art centre in Bratislava wasn’t a conflict of interest.

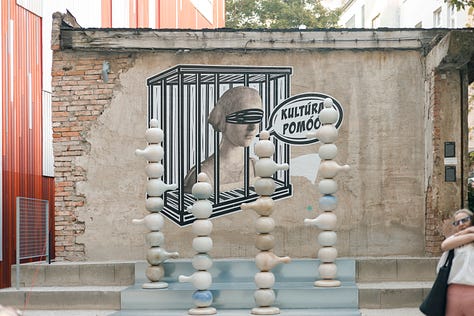

Kusá’s sacking was followed by public demonstrations at the SNG, three interim directors in short succession, the departure of over 100 curators and staff, exhibitions cobbled together with little curation, and the creation last summer of a rival symbolic protest space next door called the “Free National Gallery.”

House of ghosts

This is all meticulously documented by the Prague City Gallery exhibition, which was curated by Kusá. It’s a grim autopsy of the dismantling and hollowing out of a revered cultural institution.

Today, says Alexandra, the Slovak National Gallery is ‘a house of ghosts.’

“We’ve seen what they put on show. Just a bit of folklore, a few flags on buildings. It’s not culture. It’s cliché,” she said.

Many rooms are empty or sparsely filled, she told me. There are no major exhibitions planned. Most artists have shunned the gallery. Visitor numbers have fallen to a trickle. International partners have withdrawn.

The Culture Ministry’s remit in both countries extends to the national broadcasters.

In Slovakia, Šimkovičová has already overseen a process of bringing Slovak TV and Radio under much tighter government control through ‘restructuring’.

There were public protests by staff and civil society groups when the previous broadcaster - RTVS - was shut down. It was promptly reopened with a new director and a new name; STVR.

Prominent journalists and editors left. Others were fired by the new management. A friend told me she and her colleagues were feeling increasingly numb and frustrated at the limitations placed upon them.

Many employees of Czech TV and Czech Radio worry the same fate awaits them. The Babiš government has pledged to scrap the licence fee and replace it with direct funding from the state budget.

Fears for the stations’ editorial independence from politicians are mounting. A petition campaign is already underway, calling for the principles of public broadcasting to be upheld.

Thanks for a great meeting

Martina Šimkovičová was in Prague recently to meet her Czech counterpart Oto Klempíř, formerly a member of the Czech funk band J.A.R.

He caused some alarm by telling reporters afterwards that the Slovaks “had a head start” in reforming their funding of public media. She’d advised him on what ‘pitfalls’ to avoid, he said.

In December Klempíř expressed support for keeping the licence fee. By January, however, he was talking about full abolition perhaps as soon as 2027.

The head of the Prague City Gallery Magdaléna Juříková told me that was one reason why they had decided to host the exhibition. To show how quickly open societies can buckle under pressure from populism and far-right extremism.

To those who say - ‘well the Czech Republic isn’t Slovakia, Babiš isn’t Fico’, Alexandra Kusá has a stark message:

“That’s what we told ourselves in 2023 - ‘Slovakia isn’t Hungary. Fico isn’t Orbán.’

“Now look at us.”

Free National Gallery. Description of a Struggle runs at the Prague City Gallery’s Dům fotografie until March 29.